I feel sorry for the general public that is presented with views by bank economists, supposed experts in their field, which are too often poorly founded and wrong.

Recently—after an exciting morning replacing window hinges and sawing firewood—I sat down to lunch phone in hand so I could peruse emails and news stories, etc.

In a report covering the latest tourism and migration data by a certain bank economist (I won’t name them) the following statement jumped out at me:

“With few domestic growth drivers on the horizon (outside of a strong primary sector and increasing incomes from inbound tourism), the RBNZ will need to maintain low OCR settings to rev the economy up and to start eroding still-abundant spare capacity in the NZ economy.”

Bank economists do some useful things, like at times providing helpful insights into official data releases.

(Case in point: not long ago Michael Gordon of Westpac released a great report highlighting why the 0.9% fall in GDP Stats NZ reported for Q2 was inaccurate. I congratulated Michael and we had a nice exchange.)

But I’ve read misguided comments by many over the years.

They release and provide commentary on a range of business, consumer, and other surveys, and too often misinterpret the survey findings.

Bank economists also provide insights into prospects for the economy.

This is where my respect for them wavers, because of simple things like not sorting out which drivers of economic growth are most important. The quote above being one example.

Are there really few domestic growth drivers on the horizon?

The two mentioned in the quote—the primary sector and inbound tourism—are relatively modest in the context of what drives cycles in economic growth.

The big drivers in order of strength are interest rates and migration.

Migration is low—although that should improve next year as economic growth improves; encouraging more immigrants and adding to the already started fall in emigration.

But what about the huge fall in interest rates we've experienced since the peak in late-2023?! No mention of it in the report.

The average mortgage rate offered by banks peaked at 7.3% in October 2023, but is now 5%. That translates to a roughly 32% fall in interest costs.

Any economist worth his or her salt should know it takes some time for the boost to domestic spending and GDP from falling interest rates to filter through the economy.

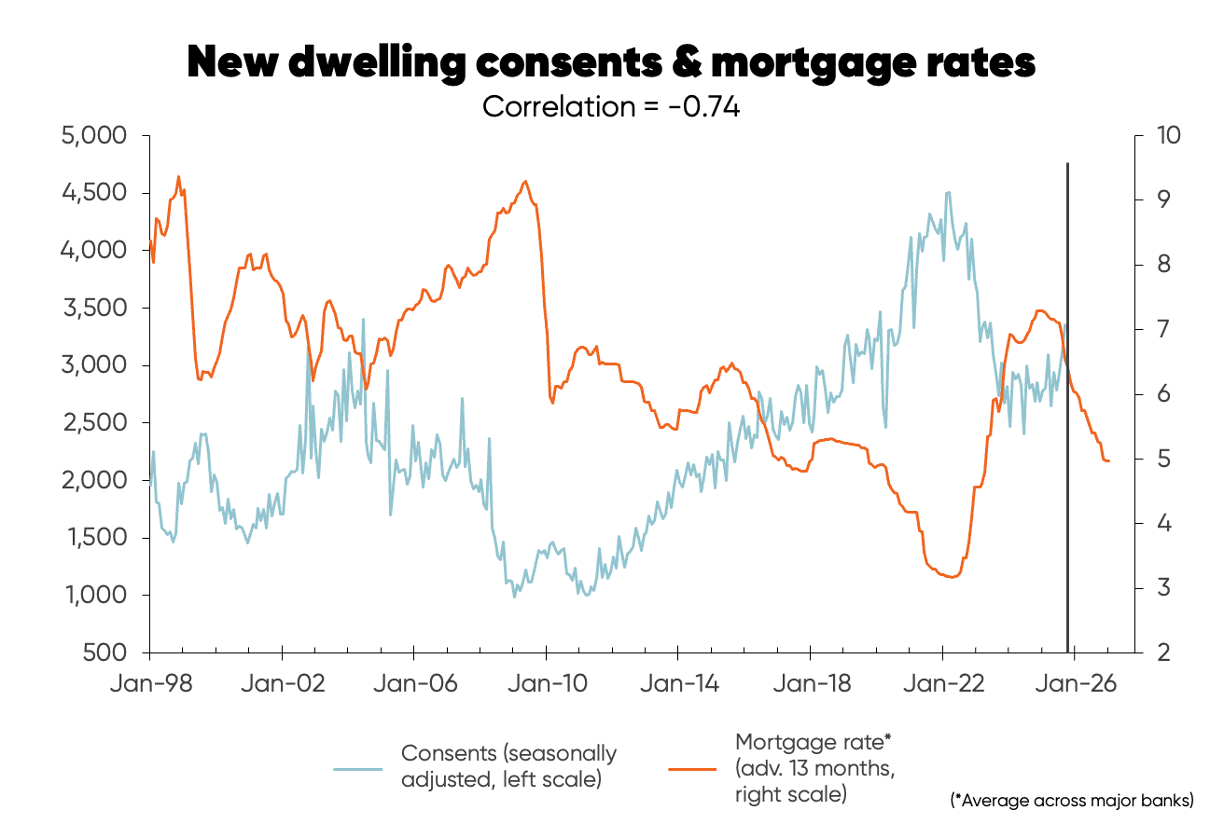

In the case of new dwelling consents, it takes 13 months as shown in the first chart below, where the orange mortgage rate line is advanced or shifted forward by 13 months.

In other words, consents for new dwellings are only just now starting to respond to the earlier falls in mortgage interest rates.

Consents can be volatile from month-to-month, but they should climb quite a bit over the next year or so—albeit potentially less than in past upturns.

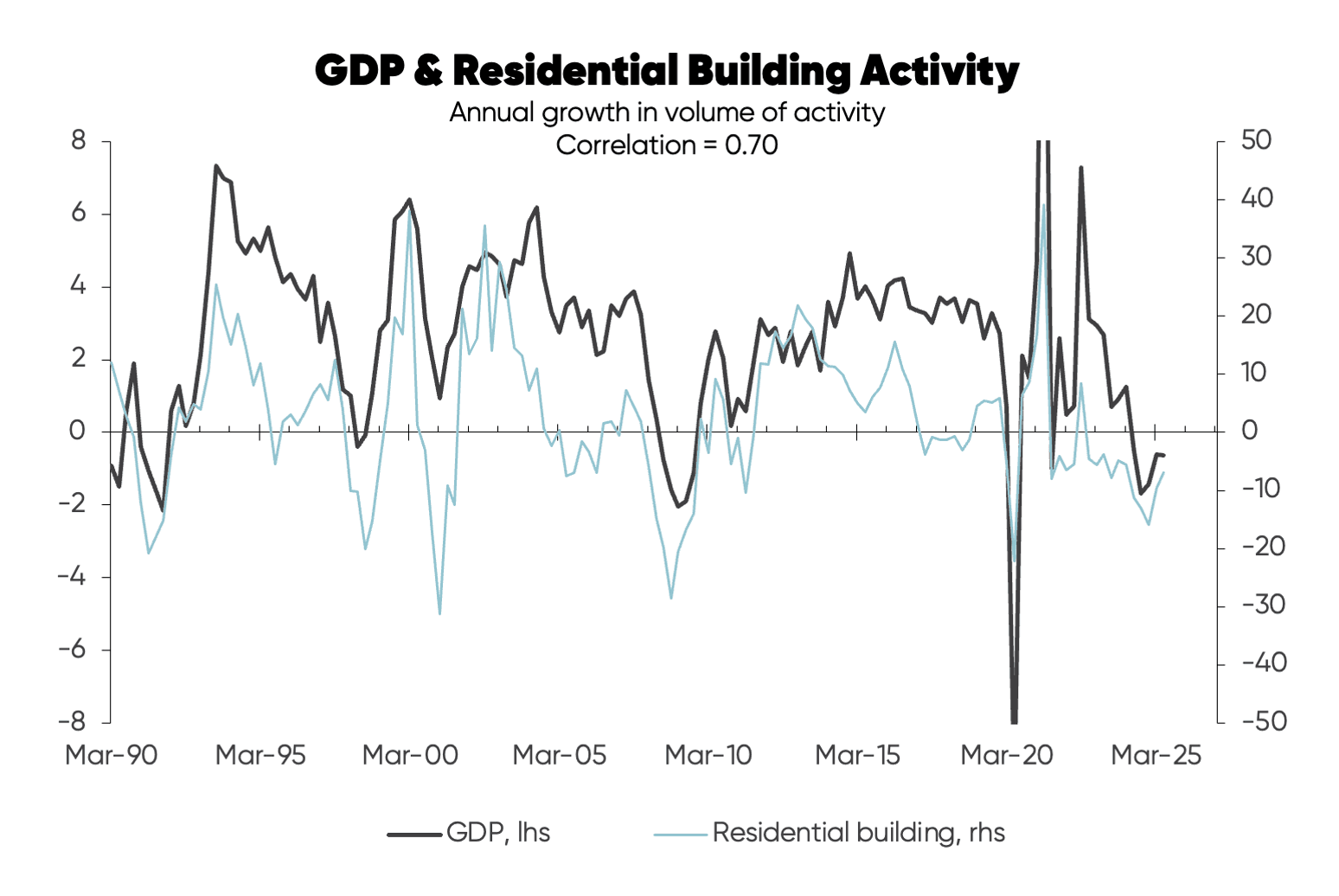

And whenever there is a solid rebound in residential building activity, like that in the pipeline, GDP growth almost without exception experiences a surge as the next chart shows. This works both ways.

To my knowledge, I was the only economist to predict that residential building activity would fall 20% a couple of years ago thanks to analysis such as that in the chart above—and I was the only economist who forewarned we were heading into a recession based on feedback I’ve had from a client who monitors what economists predict.

To forewarn is to predict in advance of it happening, not observe what's happened after the fact—bank economists do too often.

Economics is not a dismal science even though the bank economists do their best at times to make it look like it is.

By Rodney Dickens, Managing Director, Strategic Risk Analysis Ltd www.sra.co.nz.