What really drives house prices?

House prices are a hot topic. Not just here in New Zealand, but in most first world nations. Australia, UK, US, NZ, Europe have all experienced significant house price appreciation, particularly over the past two decades.

There are several local, or micro, factors that contribute to ever increasing home values:

- Population growth that is not matched with increased housing infrastructure creates a supply / demand imbalance.

- Restrictions around the availability of land for development.

- Favourable tax treatment for property investors.

- Increased urbanization.

- Changing characteristics of the family unit (separation, divorce).

- Regulations, legislation and bureaucracy.

- Construction materials and labour cost inflation.

- Monetary policy.

These are all valid reasons for house price appreciation, but I would argue that they are, for the most part, short-term and non-systematic.

Let’s look at what houses really are. They’re assets. Long term in nature and low risk. How do markets normally price long-term, low risk assets? By discounting the future cash flows, using a benchmark, long-term, risk free rate of return.

The best proxy we have for this discount factor is the US long bond yield.

Here’s how the US long bond has performed. You’ll see long dated Treasury yields have fallen from 6.86% (Jan 2000) to 2.55% Aug 2017).

A long-dated asset (perpetual security), purchased in January 2000 for $100 is worth $256 now.

Apply this same logic to housing. On the basis that housing is a long term, low risk asset class. $100 invested in housing in Jan 2000, with an initial gross yield of 6.86% should be worth c. $256 today.

Let’s have a look at some housing market performances over the same period.

United States – gross movement 193%

United Kingdom – gross movement 254%

New Zealand – gross movement 310%

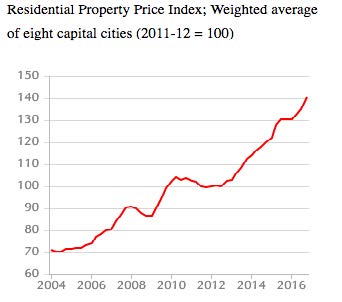

Australia – gross movement (from 2004) 200% - you get the picture.

These housing markets exhibit remarkably similar price trajectories and are in-line (more or less) with the long-term asset pricing methodology. The US lags a tad, due to extended impact of the Global Financial Crisis.

I surmise that house price inflation is a global phenomenon and it is predominantly driven by the systematic influence of long term risk-free yield.

Governments and local authorities can tinker at the edges of the housing market. These adjustments can produce minor changes in the behaviour of housing market; case in point, the NZ Loan to Value Ratio restrictions. However, you can’t around the notion that the beating heart of the housing market is uncontrollably influenced by global risk free yields, that drive long term assets prices. Government intervention, unless all-controlling, is ultimately futile.

Yes, houses are expensive. But, the maths suggests they’re about right. The big question is what will happen if / when long term treasury yields reverse their long run trend?

Top Reads:

- Compare NZ Interest Rates

- Mortgage Calculator - How Much Can I Borrow?

- How to Buy a House NZ

- Getting Started - First Home Buyers

Receive updates on the housing market, interest rates and the economy. No spam, we promise.

The opinions expressed in this article should not be taken as financial advice, or a recommendation of any financial product. Squirrel shall not be liable or responsible for any information, omissions, or errors present. Any commentary provided are the personal views of the author and are not necessarily representative of the views and opinions of Squirrel. We recommend seeking professional investment and/or mortgage advice before taking any action.

To view our disclosure statements and other legal information, please visit our Legal Agreements page here.